The Cut-Outs of Henri Matisse

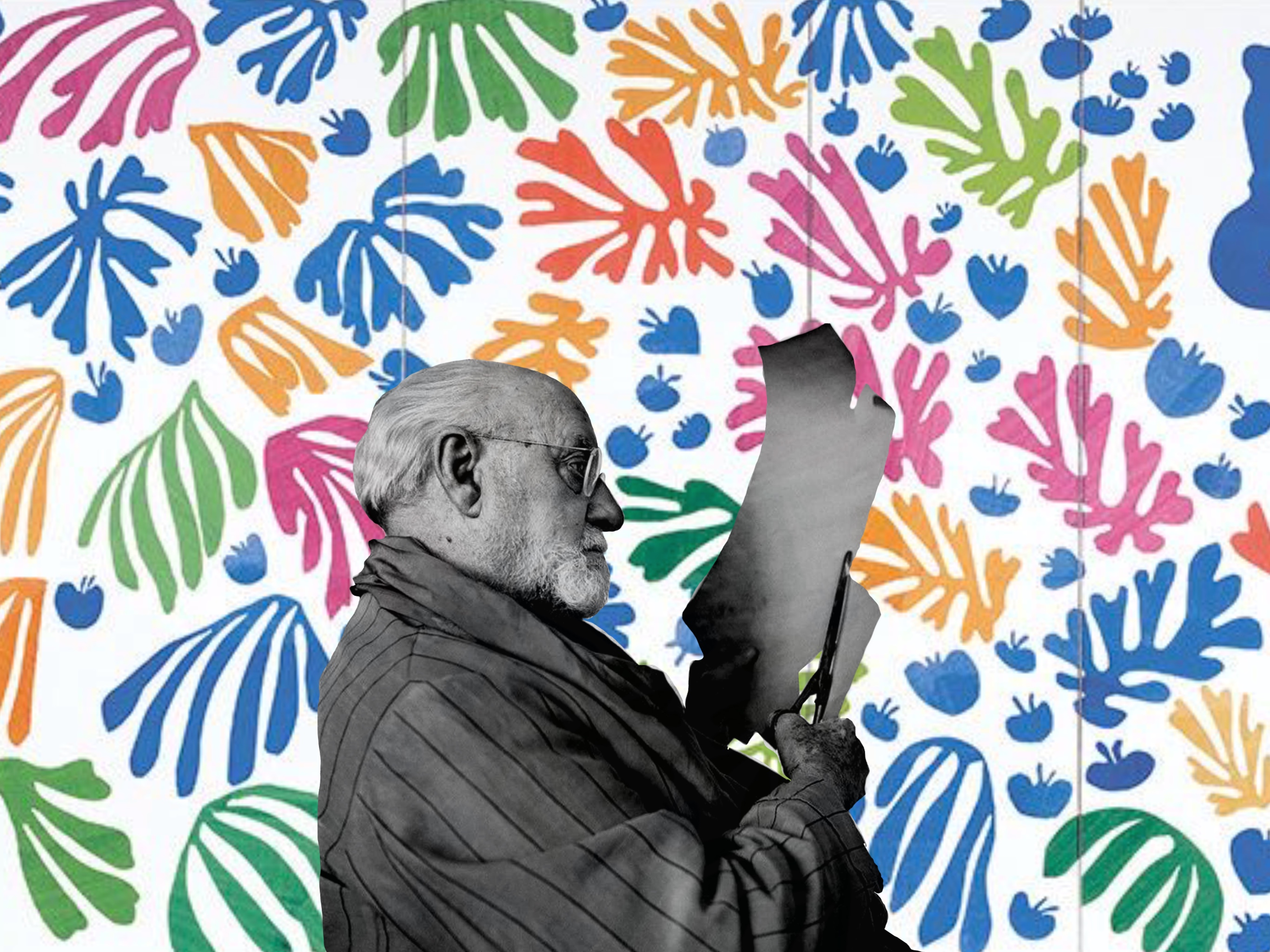

When Henri Matisse could no longer stand at the easel, he picked up scissors. What followed was a celebrated career with a radical shift that gave birth to a new way of seeing.

The Cut-Outs, or gouaches découpées, emerged during the last decade of his life. Sheets of paper, hand-painted with gouache, were cut into bold forms—leaves, coral, dancers, abstract waves—and assembled into compositions that feel both fluid and precise. The process left behind the structure of sketching altogether. The scissor became the instrument of thought.

These works weren’t about adapting to limitation—they became a full-bodied reinvention. Matisse began working directly with colour, treating painted paper as a substance.

“Cutting directly into colour,” he called it—a phrase that captures both urgency and intent. The forms he created evoked a sense of belonging. In The Snail (1953), irregular colour blocks spiral with a quiet sense of logic, like memory taking form. In Blue Nude II (1952), the figure emerges through curve and silhouette, distilled to its essence, entirely present. The restraint in form brings a kind of fullness, shaped by clarity.

The echoes of his earlier works move through the Cut-Outs with quiet certainty. The flowing curves from his figure paintings, the simplified bodies of his sculptures, and the bold colour pairings from his early modernist canvases—all reappear, pared down but pulsing with life. What once required details and structures now arrived through shape alone. It was as if everything he had studied, drawn, and painted was returning in purer form—distilled, reimagined, and finally set free.

This radical late style unfolded in collaboration. Matisse’s studio, once filled with canvases and brushes, slowly transformed into a garden of colours. Assistants helped paint and prepare the paper, pinned cut shapes to the walls under his direction, and created what he called his palette of forms. They arranged and rearranged compositions across vast walls and folding screens, turning his workspace into a living artwork. The artist directed from bed or wheelchair, surrounded by shifting flora of his own making.

Two of his most expansive works, Oceania (1946) and The Parakeet and the Mermaid (1952), show the cut-out technique at its most lyrical. In Oceania, silhouettes of coral, birds, and sea life float across a white field—spaced with care, in a quiet rhythm. The work began as a practical gesture, originally created to hide a mark on the studio wall. But over time, it grew into something contemplative and immersive—a composition that feels suspended in breath. Its motifs later reappeared in textiles and decorative fabrics, as if the simplicity of those cut forms could flow beyond canvas into daily life.

The Parakeet and the Mermaid turns an entire wall into a garden of vivid, simplified forms. Despite its scale and colour, it remains balanced and spacious. Matisse once called it “a little garden all around me where I can walk.” Created from his bed, the piece became a paper garden shaped by joy, movement, and need.

As he once said, “There are always flowers for those who want to see them.” In these final years, he didn’t just look for the flowers—he made them, in shapes and shades that floated across entire rooms.

Layering became central to this new language—not just physically, but emotionally. Shapes overlapped with intention, often hovering, leaving visible edges and shadows that created a rhythm between flatness and space. This sense of layering allowed the works to breathe. One could see the composition being made in real time, presented with its process intact. This visible layering gave each piece a kind of translucence of thought—as if nothing was ever truly finished, only resolved enough to rest.

A fine balance of freedom and control moves through these works. The colours feel instinctive, sometimes flat and unblended, while their placement reveals discipline. Matisse worked slowly, listening to how the forms responded to each other. Critics such as John Elderfield described this as “drawing with scissors”—an idea that holds both precision and movement. Art historian Jack Flam observed that the Cut-Outs carry the intensity of a lifetime spent searching for visual clarity. Their apparent ease conceals a mature rigor. These are not whimsical experiments, but distilled conclusions—crafted through years of seeing, simplifying, and choosing what to leave behind.

His colour choices, too, shaped what was to come. Matisse’s palette in the Cut-Outs—vivid, unapologetic, often unblended—paved the way for future movements that embraced colour as content. One can trace their influence through post-painterly abstraction, colour field painting, and the bold flatness of Pop Art. What he once applied in oil with nuance, now became committed to paper with clarity. These hues no longer described things.

Some questioned the classification of these pieces. Were they paintings, or collages? Decoration, or fine art? Those questions eventually fell away. Today, the Cut-Outs are seen as a turning point—a culmination that doesn’t repeat what came before. The Tate’s landmark 2014 retrospective described them as “a glorious final chapter,” while curator Nicholas Cullinan considered them a “A second life. Not a winding down, but a sudden burst of vitality.”

Matisse once spoke of seeking “a form reduced to the essential through greater absoluteness and greater abstraction.” In the Cut-Outs, that search arrives at its most distilled state. These are works that let colour hold its own space, and let forms breathe without explanation. In the face of physical constraint, his vision expanded with new freedom. Through these floating compositions—joyful, balanced, intuitive—he offered a final body of work that remains radiant and complete. A life’s clarity, cut into colour.